Edward Curtis Memorial to a Culture

LiveAuctionTalk.com

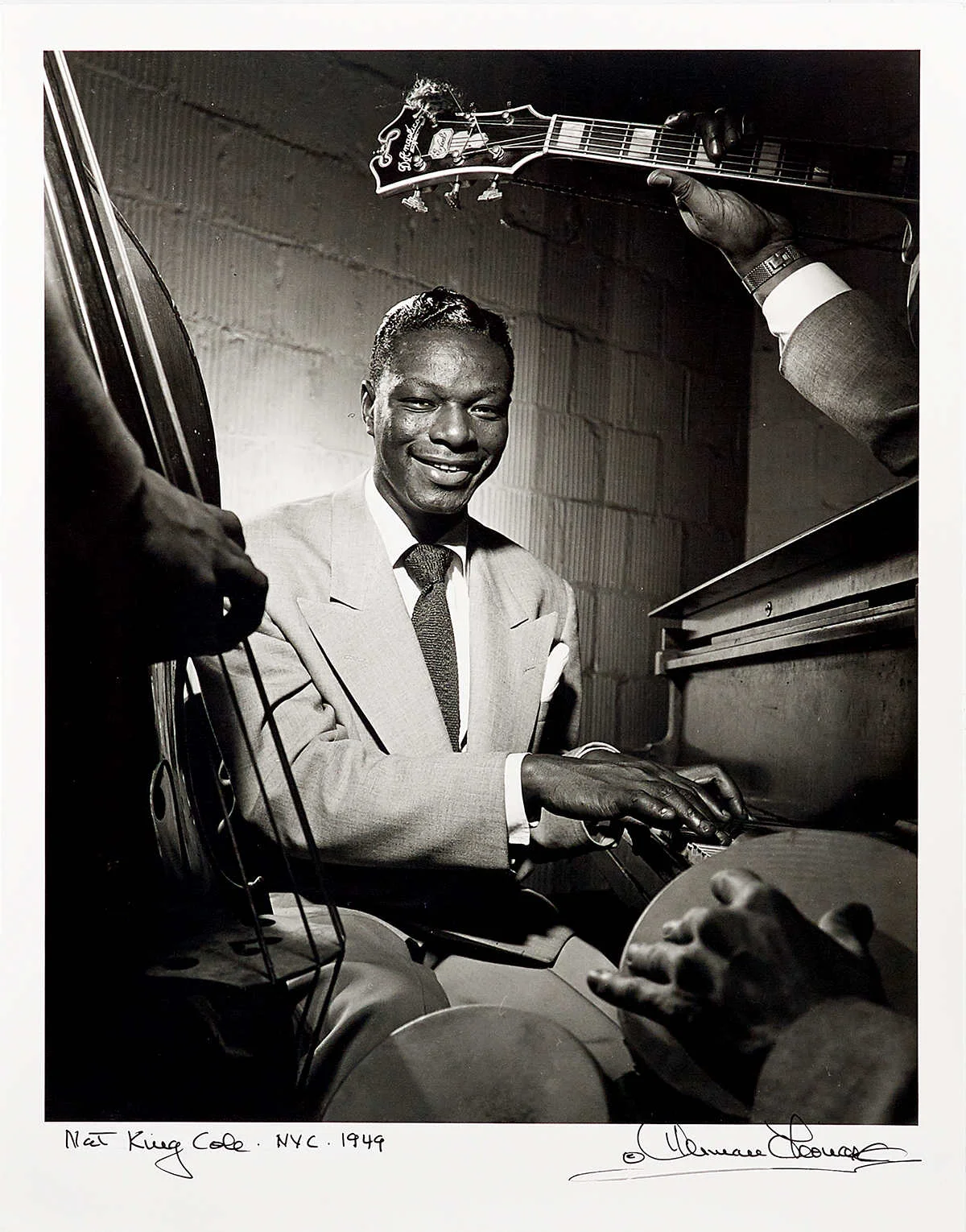

Photo courtesy of Brunk Auctions.

From the late-19th century through the 1920s Edward S. Curtis studied and photographed the indigenous peoples of North America. An enormous undertaking.

War and disease annihilated so much of the Native culture and like so many of his contemporaries Curtis believed he was capturing a “vanishing” race.

“The spirit of the Native people, the first people, has never died. It lives in the rocks and the forests, the rivers and the mountains. It murmurs in the brooks and whispers in the trees…their voice can never be silenced.”

His book “The North American Indian” was one of the most ambitious books ever undertaken by a single person. He created over 40,000 negatives of Native Americans on glass plates. The final published work was 20 volumes.

Curtis was also a product of his culture. He believed he was honoring the tribes he captured on film by amassing a huge photographic “memorial” to them. He wanted to present them the way they looked before the white man showed up and believed he was in a race against time.

Unfortunately, by the time Curtis arrived few Native people still lived the traditional ways of life. He went out of his way to find isolated groups who were still living relatively traditional lives. In that sense his photos are historical documents.

“The passing of every old man or woman means the passing of some tradition, some knowledge of sacred rites possessed by no other...consequently the information that is to be gathered, for the benefit of future generations, respecting the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind, must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost for all time,” he said.

Curtis didn’t like seeing the Natives moved onto reservations. He didn’t like seeing their religious ceremonies and languages outlawed. And he didn’t like seeing the children shipped off to boarding schools. He also did nothing to stop it.

The photographer was so convinced the Natives were about to disappear he created a stereotype of them: Indians riding off into the sunset, Indians with pots on their heads, and Indians in giant headdresses.

He also doctored his images removing any indications of a “modern” Indian. He posed them and dressed them in costumes. Few of his Natives smile. The viewer is often presented with the image of a “stoic” culture lacking depth.

Curtis said he wanted to make them live forever through his images. His way of accomplishing that was to romanticize them.

At the same time 40,000 images of North American Indians would not exist without Curtis. He may have dressed the Natives up but a closer look at their faces reveals the wisdom and character of these people. Costuming didn’t cover it up.

The spirit of the indigenous people shows up powerfully. The photographer’s eye lingers long enough to capture that spirit.

“The spirit of the Native people, the first people, has never died. It lives in the rocks and the forests, the rivers and the mountains. It murmurs in the brooks and whispers in the trees…their voice can never be silenced,” said writer Kent Nerburn.

On July 20, 2019, Brunk Auctions featured a selection of Curtis contemporary limited edition prints in its auction.

Here are some current values.

Edward S. Curtis Contemporary Limited Edition Prints

Oasis in the Badlands; Goldtone edition; 30 of 150; 18 inches by 22 inches; $1,000.

Crater Lake; Goldtone edition; 26 of 100; 18 inches by 22 inches; $1,140.

A Son of the Desert; Goldtone edition; 3 of 8; 24 inches by 20 inches; $1,500.

Original Curtis Photo:

Oasis in the Badlands; signed lower right Curtis; 1905; 5 7/8 inches; by 7 ¾ inches; $6,765.